THRILLING SPACE ADVENTURE IN THE YEAR 2016

By

Allen M. Steele

It’s the early 21 st century, and the worlds of the solar system are again in peril.

In this plane of the multiverse, the imaginary one described in countless stories by countless writers, nearly all of Earth’s neighboring planets, moons, and asteroids are habitable and inhabited. From the rocky, sun-roasted badlands of Mercury to the jungles of Venus, the red deserts and canals of Mars to the mountains of Jupiter and the cities of Saturn, the oceans of Neptune to the landscapes of Pluto, the solar system teems with humankind and its cousins: green-skinned Martians, red-skinned Venusians, hulking Jovians, blue-skinned Saturnians, the amphibious denizens of Neptune, the dwarves of Ceres. Spaceships traverse the vast distances between these planets in only minutes though their engines are nothing more than vaguely-described “rocket tubes.” There are even interplanetary spaceship races where the fastest vessels in the system compete to see which one can complete a circular course between Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars in the shortest number of hours. However, no one has yet left the solar system to roam the galaxy, although a gnome-like Martian scientist is secretly developing a hyperdrive that will not only propel a craft faster than light but even transport it back through time. The only world that doesn’t support a population – at least not to anyone’s general knowledge – is the Moon, aka Luna. Even though it is Earth’s closest neighbor, no one lives in its stark, airless wastelands. Or so it’s generally believed. But now, evil once again threatens humans — or “Earthers” as the inhabitants of the third planet are usually (and sometimes resentfully) known by the other races — and the law-abiding members of its extraterrestrial cousins. It may be a masked villain like the Wrecker or the Life Lord who has come up with another means of extorting credits from his victims. It may be a previously unknown race inhabiting the core of Halley’s Comet, or the secret catacombs of the Moon’s far side. It could even be descendants of the mysterious Denebians, long-lost members of a distant extrasolar race that came to Earth one million years ago, then vanished, leaving behind eldritch relics reminiscent of ancient black magic.

In this plane of the multiverse, the imaginary one described in countless stories by countless writers, nearly all of Earth’s neighboring planets, moons, and asteroids are habitable and inhabited. From the rocky, sun-roasted badlands of Mercury to the jungles of Venus, the red deserts and canals of Mars to the mountains of Jupiter and the cities of Saturn, the oceans of Neptune to the landscapes of Pluto, the solar system teems with humankind and its cousins: green-skinned Martians, red-skinned Venusians, hulking Jovians, blue-skinned Saturnians, the amphibious denizens of Neptune, the dwarves of Ceres. Spaceships traverse the vast distances between these planets in only minutes though their engines are nothing more than vaguely-described “rocket tubes.” There are even interplanetary spaceship races where the fastest vessels in the system compete to see which one can complete a circular course between Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars in the shortest number of hours. However, no one has yet left the solar system to roam the galaxy, although a gnome-like Martian scientist is secretly developing a hyperdrive that will not only propel a craft faster than light but even transport it back through time. The only world that doesn’t support a population – at least not to anyone’s general knowledge – is the Moon, aka Luna. Even though it is Earth’s closest neighbor, no one lives in its stark, airless wastelands. Or so it’s generally believed. But now, evil once again threatens humans — or “Earthers” as the inhabitants of the third planet are usually (and sometimes resentfully) known by the other races — and the law-abiding members of its extraterrestrial cousins. It may be a masked villain like the Wrecker or the Life Lord who has come up with another means of extorting credits from his victims. It may be a previously unknown race inhabiting the core of Halley’s Comet, or the secret catacombs of the Moon’s far side. It could even be descendants of the mysterious Denebians, long-lost members of a distant extrasolar race that came to Earth one million years ago, then vanished, leaving behind eldritch relics reminiscent of ancient black magic.

When this happens and it comes to the attention of James Carthew, the President of the Solar Coalition, he has an option: launch a rocket from the North Pole, one that will explode brilliantly enough that it can be seen from somewhere on the surface of the Moon.

This is done, and just as expected, the explosion is spotted by the inhabitants of a secret base beneath the floor of the crater Tycho. Within just minutes, the doors of a hidden underground hangar open, and up leaps a unique, teardrop-shaped spacecraft: the Comet, famous throughout the system as the fastest ship in space.

As the Comet races for the President’s skyscraper headquarters, its crew braces themselves for their next mission to maintain law and justice in space. They are the oddest team in the solar system: a pale-skinned, pink-eyed android named Otho, a giant iron robot named Grag, a disembodied human brain within a transparent, life-sustaining cube who was a scientist named Simon Wright but is now more commonly called the Brain … and their leader, the young red-haired adventurer the three of them adopted as an orphaned infant and raised to be the greatest hero in the nine worlds of the Sun.

Captain Future, the Man of Tomorrow.

* * *

Captain Future was unique among the heroes of the Pulp Era. There were other champions of space during the 30’s and 40’s: Kimball Kinnison of Edward E. Smith’s Lensman novels and Hawk Carse of the short-lived series of space adventures by the pseudonymous Anthony Gilmore, both of which appeared in Astounding during the 30’s; the groundbreaking but now obscure Professor Jameson series by Neil R. Jones that was published in Amazing in the late 20’s through 30’s; and of course the comic strip and movie serial heroes Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, the latter introduced in a pair of novellas published in Amazing in 1928 and later adapted to daily comics by author and creator Philip Francis Nowlan.

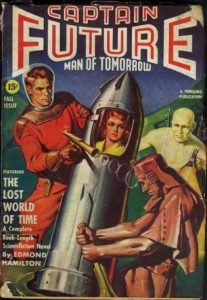

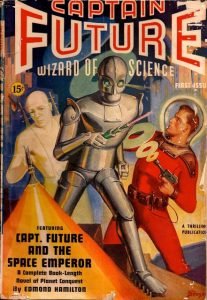

But Captain Future was different. He was the only space adventurer to have his own magazine, Captain Future — Wizard of Science (the subtitle was later changed to Man of Tomorrow). And although many of the other pulp heroes frequently had plots, devices, and characters that had a science fiction look and feel to them — Doc Savage in particular, but also The Shadow, Operator 5, and G-8 and his Battle Aces — Captain Future was the only straight-out science fiction (or “scientifiction”, to use the genre’s original name) character. This alone made it stand out among the science fiction of the time … for better or worse.

Captain Future was one of the last major characters to be introduced during the Pulp Era. By 1939, nearly all the pulp magazine publishers had single-character hero pulps; one of the few exceptions was Better Publications, which also published two science fiction magazines, Thrilling Wonder Stories and its recently-launched sister Starling Stories. These two scientifiction pulps were at the lower end of the SF market, but they sold well enough that, when Better’s editorial director Leo Margulies finally decided to get into the hero-pulp game, he chose to make it a SF character since there wasn’t already one being published by his competitors.

When Margulies and his editor, Mort Weisinger, sat down to brainstorm a science fiction hero, they cobbled together a character called Mr. Future. As ideas for pulp heroes go, Mr. Future was …well, interesting. “The Wizard of Science” was originally conceived to be a dwarf with a grotesquely oversized head who lived at the top of the world’s tallest building. He had three companions: a giant robot called Grag, an old scientist named Simon Wright who could recall every scientific fact he learned, and an alien warrior named Otho who inhabited a ring on his finger. Mr. Future would later be changed to a red-headed adventurer named Captain Future, but the supporting cast remained unchanged.

With this rough concept in mind, Margulies and Weisinger set forth to find a writer to flesh it out and turn it into a regular series. Although legend has it that one person they approached was Lester Dent, the writer mainly responsible for creating Doc Savage (Dent was busy with Doc, though, and declined), the person they settled on Edmond Hamilton, then the preeminent author of space adventure (the term “space opera” hadn’t yet been coined). Nicknamed “World Wrecker Hamilton” by SF fans for his tendency to destroy planets and suns in his stories, Hamilton was the perfect choice for this series.

Indeed, Hamilton probably saved the character from the people who originally came up with him. When Weisinger and Margulies gave him the prospectus for Captain Future and his companions, Hamilton would recall many years later in a biographical essay, he realized:

“These three characters would be very hard to use in a story, and suggested changes in them. Simon Wright became an aged scientist who, about to die, had his living brain transferred into an artificial serum-case and was known as the Brain […] Otho became an android, a living man of synthetic flesh created in their moon laboratory by the Brain and Captain Future’s father. And the automaton became Grag, an intelligent robot, who was not very bright but immensely strong and very faithful.”

As for Captain Future himself, he has an unusual backstory. His real name is Curtis Newton and he was the child of a brilliant scientist, Roger Newton, and his wife Elaine. Roger Newton and the Brain were working to develop Otho when they made the decision to flee to the Moon, an uninhabited and seldom visited backwater, in order to escape from the villainous Victor Corvo, whom Hamilton originally described as “an unscrupulous politician with sinister ambitious” who wanted to get his hands on the prototype android (in later stories, Hamilton inexplicably changed Corvo into a gangster). The Newtons and Dr. Wright, Roger’s mentor, established a secret laboratory beneath Tycho Crater. Here they built Grag, transferred Dr. Wright’s brain into the serum case, created Otho, and when Roger and Elaine had a little time to spare, Curtis was conceived and born.

Unfortunately, Corvo didn’t give up his pursuit of Dr. Newton and his family. He eventually tracked them to the Tycho moon lab, where during the violent confrontation that followed, Corvo killed Roger and Elaine Newton. In retaliation, the Brain ordered Grag to kill Corvo, yet the tragedy was finished: Curt’s parents were dead and the infant became an orphan. Before she succumbed to her injuries, though, Elaine Newton put her baby in Dr. Wright and Otho’s care, instructing them to raise him in secret on the Moon with a purpose in mind:

“I seem to see little Curtis a man,” she whispered her eyes raptly brilliant. “A man such as the System has never known before — fighting against all enemies of humanity.”

And with this in mind, the Brain, Otho, and Grag commence the long task of raising young Curt to be a two-fisted scientist and adventurer. And in time, when he reaches adulthood and sets out to fulfill the destiny his mother imagined for him, Curt takes on the name Captain Future.

* * *

All this is recounted in the first Captain Future adventure, Captain Future and the Space Emperor (originally titled The Horror on Jupiter), published in the Winter 1940 issue of Captain Future — Wizard of Science. In the premiere story, it’s stated that these events occurred in June, 1990. This is laughable today, but recall the era when this story was written. Nothing had yet been launched into space, and all anyone knew of the solar system came from what could be viewed through an observatory telescope lens. Thus the worlds beyond Earth were largely unknown and filled with mystery; anything was possible, so science fiction writers had plenty of latitude to imagine, improvise, and extrapolate at will.

The pulp writers of the 30’s freely borrowed ideas from one another; no one ever considered filing lawsuits for theft of copyrighted material or infringement of intellectual property. So it’s quite obvious that Captain Future took quite a bit from Doc Savage; in fact, in a later adventure, Edmond Hamilton named a character Lester Dent after the friend and colleague hiding behind the Kenneth Robeson house name. And since Hamilton would later go on to write scripts for DC Comics (then called National Comics), it shouldn’t be a surprise that Captain Future’s origin — a boy whose parents are killed by a criminal and grows up training himself to fight evil — closely resembles that of Bruce Wayne and Batman, who’d been introduced in Detective Comics just a few months earlier.

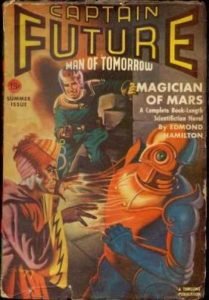

Like Doc Savage, Captain Future had an unusual crew. Like Doc Savage, he is a man of mystery, known throughout the solar system and feared by criminals from Mercury to Pluto, yet nonetheless an enigma. But there are also certain similarities between Captain Future and Batman. Just as Commissioner Gordon would summon Batman by shining the Bat-Signal against the clouds above Gotham, the President of Earth would let Captain Future know that he was needed by ordering a rocket packed with explosives to be launched from the North Pole (why the President couldn’t simply use a radio was never explained). Batman had the Batcave; Captain Future had the Moon lab. And shortly after Bruce Wayne gained a young ward named Dick Greyson, aka Robin the Boy Wonder, for one adventure, The Magician of Mars (CF Summer/41) Curt Newton was briefly joined by a teen sidekick, Johnny Kirk (who mercifully disappeared after that single appearance; Robin he was not).

The Captain Future novels were not Edmond Hamilton’s finest novels, although they have arguably become his best-known work. Like many writers responsible for supplying the content of a hero pulp, Hamilton was usually given a deadline of only two or three weeks to produce a 40,000 – 50,000 word novel (the average length of a novel today is around 100,000 words). This is despite the fact that, unlike monthly magazines like Doc Savage or The Spider (or The Shadow, published bi-weekly), Captain Future was a quarterly, published at a comparatively sedate rate of four times a year. But Weisinger, an editor largely unloved by the authors who wrote for him, gave Hamilton tight deadlines in order to maintain an inventory (although some suspected Weisinger really did this for the sadistic pleasure of making writers jump through hoops). So Hamilton almost never had a chance to produce revised second drafts of his Captain Future novels, and it showed; while many of the stories are well-written for what they are, some suffer from being rushed and are rather crude.

Nonetheless, once Hamilton hit his stride, the Captain Future novels he produced (mainly under his own byline, one of the few hero-pulp writers to do so) stand alongside the crimebusting adventures of Doc Savage, The Shadow, Operator 5, and other marquee characters of the era. Indeed, the only real difference between the Captain Future novels concerned with the preservation of law and order and those of pulp heroes taking place in contemporary times is their setting; otherwise, Captain Future and the Futuremen are just as devoted to the fight for justice in the 21st century as Doc Savage and his crew, whom they greatly resemble, are fixated on fighting crime in the 20th century.

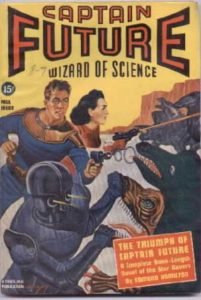

In the third novel, Captain Future’s Challenge (CF Summer/40), Curt and his crew pursue the Wrecker, a villain hiding his identity beneath an opaque space helmet who uses a pirate fleet of black spacecraft in an extortion plot to shut down the system’s sources of gravium, the mythical element used by space vessels as fuel for their engines. The next novel, The Triumph of Captain Future (CF Fall/40), concerns the hunt for the Life Lord, the secretive purveyor of an exotic drug called Lifewater, the product of a Fountain of Youth on Mercury that seemingly restores the youth and vigor of its users while also turning them into addicts (drug abuse was a common theme in the hero pulps of the time). After the Comet’s crew returns from the series first jaunt to an interstellar world in Quest Beyond The Stars (CF Fall/42), they return to our solar system in Outlaws of the Moon (CF Winter/42) to discover that their lunar headquarters has been discovered and invaded over by gangsters, who’ve taken Curt Newton’s cache of superweapons captured from previous foes and then framed Captain Future with the assassination of President Carthew.

It’s in Captain Future and the Seven Space Stones (CF Winter/41) that Curt and company meet their archenemy for the first time: Ul Quorn, a mixed-race Terran-Martian who poses as the so-called Magician of Mars in the traveling Interplanetary Circus which is actually the front for a crime ring. What follows is the familiar “carnival of crime” plot that was a standard of hero pulps and superhero comics after that, but Hamilton wasn’t done with Ul Quorn yet. Two issues later, in The Magician of Mars, he breaks out of the Interplanetary Prison on Pluto’s moon Cerberus, whereupon he launches into another criminal scheme, this time without his defunct circus. Ul Quorn is apparently killed at the end of the novel when his ship plunges into the Sun while trying to get away from the Comet, but he comes back one more time in The Solar Invasion (Startling Stories, —) one of the few Captain Future novels not written by Hamilton but, in this instance, by Manley Wade Wellman, one of the more notable writers to come out of the Pulp Era.

Hamilton wrote 17 of the original 20 Captain Future novels; along with Wellman’s novel, the other two were supplied by Joseph Samachson, who also wrote under the pseudonym William Morrison. Unfortunately, they were not always well-received by SF fans of the time nor always fondly remembered by fans in years to come. Captain Future was perfectly fine for the sort of swashbuckling space adventure popular in the pulps throughout the 30’s, but by the 40’s science fiction had begun to change in very significant ways. John W. Campbell, Jr., who (like Hamilton) had written copious amounts of space opera for Amazing during the 30’s, became the editor of its chief competitor, Astounding, in 1938. Before then, he’d begun writing a more serious-minded, less flamboyant sort of SF for Astounding under the pseudonym, including stories like “Twilight” and “Who Goes There?” that in years to come would be regarded as classics. Astounding publisher Street & Smith, also the publisher of Doc Savage and The Shadow, was considered to be the class act of the pulp circus, and Campbell persuaded his bosses that the key to Astounding successfully competitive against Amazing, Thrilling Wonder, and other science fiction magazines was to find and publish a more mature and sophisticated kind of SF.

His strategy worked. Beginning with the July 1939 issue, in which authors Robert A. Heinlein, A.E. van Vogt, and Theodore Sturgeon made their professional debuts and Isaac Asimov published his second short story, Astounding departed from the rockets-and-ray guns formula and began publishing a kind of science fiction meant more for educated adults rather than high-school kids. Fans eagerly embraced this change, and what followed over the next several years is now considered science fiction’s Golden Age, during which many works were published that have since become acknowledged classics.

All at once, melodramatic space adventures like Captain Future became old hat. The magazine’s coming debut was publicly announced during the first World Science Fiction Convention, held in New York City over the Independence Day weekend of 1939, but it was quickly overshadowed by changes taking place elsewhere in the genre. In the fanzines, Captain Future was soon unfavorably compared to Astounding even though the same fan writers who derided Captain Future likely continued to secretly read his adventures; it’s a long-held truism in SF publishing that what science fiction fans say they want and what they actually buy are two different matters.

Nonetheless, Captain Future managed to hold its own, weathering the outbreak of World War II and the temporary loss of Edmond Hamilton when he temporarily quit writing for the magazine, believing that he’d soon be drafted. Weisinger responded by hiring Samachson to supply new Captain Future novels under the house name “Brett Sterling.” Hamilton returned to Captain Future after the draft board declared him 4F, but the damage was done; Samachson’s novels Worlds to Come (CF Spring/43) and Days of Creation (CF Winter/44) were competent enough but lacked the flair of Hamilton’s novels, and although Hamilton made up for it with Magic Moon (CF/Winter 43, bylined Brett Sterling), the next issue was the last. Captain Future folded with the Spring 1943 issue, killed like so many other pulps by shrinking circulation and the wartime paper shortage.

The magazine was dead but the character lived on, at least for a little while. Captain Future’s sister pulp, Startling Stories (trumpeted on its masthead as having “A Complete Novel in Every Issue”) published Hamilton’s last two CF novels, Red Star of Danger (Startling Spring/45) and Outlaw World (Startling Winter/46) and remaining in inventory after the magazine’s abrupt cancellation; their popularity led to The Solar Invasion, the final novel-length CF adventure published in during the Pulp Era. A few years after the end of World War II, during the postwar boom the SF genre enjoyed for the first half of the 50’s, Startling revived Captain Future in a series of short stories beginning with “The Return of Captain Future” (Startling 1/50). These six stories, more sophisticated in plot, characterization, and style, bore Edmond Hamilton’s byline, but many Captain Future fans suspected that they were secretly co-authored by Hamilton’s wife Leigh Brackett, a rumor the couple neither confirmed nor denied.

Curt Newton’s return to action didn’t last very long. After the final canonical Captain Future story, “Birthplace of Creation”, appeared in Fall 1946 issue of Startling, it was believed that the series was dead, never to be seen again.

* * *

But it’s hard to keep a good space hero down. In the late 60’s, Popular Library, a lower-end paperback publisher, picked up on the rediscovery of pulp heroes that had returned Doc Savage, The Shadow, and the Spider to service and reprinted many, if not all, of the Captain Future novels and one of the short stories. But the Popular series had serious flaws; they were printed out of chronological order and often under different titles, so that the first book published, Danger Planet, was one of the last originally published, Red Star of Danger, while the last book Popular brought out was actually the first Captain Future novel, Captain Future and the Space Emperor. Likewise, two of the Ul Quorn novels, Wellman’s The Solar Invasion and Hamilton’s The Magician of Mars, were reprinted (again, out of order), but Captain Future and the Seven Space Stones, where the villain was introduced, was not. And although the first three reprints had lovely Frank Frazetta covers and the fourth, Quest Beyond the Stars, featured an striking Jeffery Jones painting, the remaining books sported covers reprinted from Germany’s weekly Perry Rhodan magazine that had nothing to do with the novels themselves.

The worst thing, though, was the timing. Popular Library brought these novels out in the midst of science fiction’s New Wave literary revolution that had recently come out of Europe and swept through American SF as well. “Space opera” was a pejorative term and the kind of “scientification” that writers like Edmond Hamilton had pioneered was largely held in contempt. Even Ed Hamilton, still alive and writing the Star Wolf series that would be his final work, seemed to regard his most famous creation with embarrassment. Popular Library abruptly stopped reprinting the series without finishing it, and once again Captain Future disappeared.

But only in America. In postwar Japan, Captain Future never vanished. Translations of Hamilton’s novels were continually in print in that country, often with eye-catching cover art (although in one early series, Grag looks like he has a mini-fridge for a head). Then in 1979, during the space-opera boom that swept through Japanese popular culture following the release of Star Wars, an animated Captain Future TV series appeared as an afternoon children’s show. Although some of the characters had been changed both in name and in likeness — for instance, Otho was now called “Otto” and looked like Popeye’s cousin — the half-hour episodes were generally faithful four-part adaptations of Hamilton’s novels (skipping the Samachson and Wellman novels), with fourteen of those novels eventually adapted during the show’s single season. It was then exported to Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Portugal, Brazil, and the US. America was the only place where the show flopped; it was badly translated, edited, and scored, and subsequently went largely unseen in the country of Captain Future’s first. On the other hand, the show was a hit in Germany and caused the Hamilton novels to be reprinted; in Japan, the anime led to the production of a long line of Captain Future toys, books, and kid’s clothing, and today both the show and the books are venerated cult classics.

In 2017, I updated and rebooted Captain Future and the Futuremen in a novel, Avengers of the Moon, followed later by a four-part paperback serial collectively titled The Return of Ul Quorn. Modesty prohibits further comment except to note that Avengers of the Moon was nominated in 2021 for Japan’s Seiun Award in the category of Best Foreign Translated Novel, and that the series as a whole has led to the rediscovery of Captain Future by American SF fans, this time more favorably than before.

In 2017, I updated and rebooted Captain Future and the Futuremen in a novel, Avengers of the Moon, followed later by a four-part paperback serial collectively titled The Return of Ul Quorn. Modesty prohibits further comment except to note that Avengers of the Moon was nominated in 2021 for Japan’s Seiun Award in the category of Best Foreign Translated Novel, and that the series as a whole has led to the rediscovery of Captain Future by American SF fans, this time more favorably than before.

Captain Future was one of the lesser heroes of the Pulp Era, never gaining the enormous popularity of the characters who shared magazine racks with him. Yet over time, he gained an international audience, and in fact, is the only Golden Age pulp hero to ever have his own TV series. He’s back … in fact, it could be argued that he never really went away.

Sometimes, playing the long game is the way to win.